While working on the series about schools, I discovered numerous interesting photos, articles, and books. I thought I would share some here.

While working on the series about schools, I discovered numerous interesting photos, articles, and books. I thought I would share some here.

The Pagoda Hill Kindergarten opened in 1883, by Miss Mary Alice Phelps, assisted by Miss Anna Warren, both graduates of Mrs. Kate Smith Wiggins’ training class at the California Kindergarten Training School in San Francisco.

“A leading School for Training the Little Ones of Oakland and vicinity“

The school was in Miss Phelps’s father’s (Coridan B. Phelps)home in Pagada Hill, near College Ave and Claremont Ave.

“derives its name from the hill it is stituated … the property having been part of the estate belonging to the late Hon. J. Ross Brown.” Oakland Tribune Jan 20, 1887

The climate was delightful and healthy.

The grounds were picturesque, and the house was large and airy.

The school aimed to make children happy, unselfish, gentle, obedient, thoughtful, industrious, and helpful.

Miss Warren was in charge of music and games. Sewing was also taught, and hot lunch was furnished to those who desired it.

In May 1883, the school purchased a handsome coach to take the children out for a daily airing. The coach held about 16 children and was also used to take them to and from school to protect them from the dangers of the streets.

...excellent care taken of the children and the good manors in which they are schooled both at then table and elsewhere”

The school moved to 1513 Telegraph Ave (corner of 21st) because they needed more room.

Then the school moved back to Pagada Hill in 1886.

I’m not sure how long the kindergarten was in business. I have found ads up to 1887.

Mary Alice Phelps died in 1944.

Pagada Hill was the name of a mansion owned by J. Ross Brown in the Claremont District.

In researching Montclair (a district in Oakland), I have come across many interesting stories. Here is one of them.

In a 1976 article in The Montclarion, entitled “Old Timer Reminisces,” Walter Wood discusses growing up along the shores of Lake Temescal.

“Montclair was wild as a hawk,”

Walter Wood

Walter was born in 1887 in a small, four-room house near the corner of 51st and Broadway, which his father had built and later torn down to make room for the widening of 51st. His father died in 1886 before Walter was born.

When Walter was attending school, he lived with his mother and stepfather, George W. Logan. They lived on a farm alongside Lake Temescal, where Logan was the caretaker and superintendent for Contra Costa Water Company’s filtration plant, which supplied Oakland’s drinking water.

Walter started school at the age of eight in North Oakland. Wood attended Peralta School until fourth grade. From 1899 to 1904, he attended Hays Canyon School, where he completed grades five through nine.

Walter and his seven brothers and sisters walked from Lake Temescal to Peralta School in North Oakland.

The Hays Canyon School (where the old Montclair firehouse is) was located two miles from the lake when they walked there in the early 1900s. Sometimes, remember Wood, they rowed a boat to the other end of the lake and walked from there.

The school was a beautiful Victorian one-room building with a bell and a cupola. There was room for forty students and one teacher.

When Walter was 11, he was a mule driver with the crew that dug the first tunnel (Kennedy Tunnel) from Oakland to Contra Costa County. He spent a summer working on the project, earning him the honor of being the first person through the tunnel. He was near the front when they broke through, and a man who looked after Walter gave him a shove and pushed him through.

On a typical Day in 1899, Walter Wood would wake up on the farm and, after breakfast, do an hour’s worth of chores.

In addition to their regular chores, the Wood and Logan children were assigned the duty of weed-pulling on the Temescal dam. If weeds grew on the side of the dam, squirrels would dig into the barrier, causing damage.

Playtime came on Saturday afternoons and Sundays. Wood and his siblings had run the area, as it was completely undeveloped except for a few farms.

One of the farms was the Medau Dairy, which is now Montclair Park.

George W. Logan started working for the Contra Costa Water Company (now EBMUD) as the Superintendent of the Lake Temescal dam in 1888.

Logan worked at Lake Temescal for 18 years, transferring to Lake Chabot in 1904, and retired from the company in 1916.

George William Logan (1842-1928) was born in Canada in 1842. He came to California in the late 1880s.

Logan was married twice, first to Elizabeth Robinson (1845-1886)in 1884, and they had a daughter, Jessie, and a son, Maurice. Elizabeth died in about 1886 or 87.

His second wife was Mary Jane Hayden Wood (1860-1958); they had eight children, five of whom were hers and two of whom were his, and one child together.

Maurice (1886 -1977) was an American watercolorist, commercial artist, arts educator, a member of the Society of Six, and a professor at the California College of the Arts in Oakland.

Logan grew up on the shores of Lake Temescal with his father, George Logan, stepmother, and brothers and sisters.

Later in life, he resided on Chabot Road, near Lake Temescal.

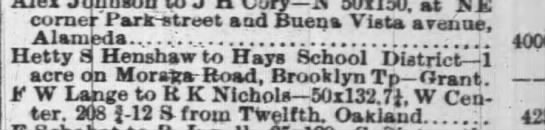

In March 1886, the Board of Supervisors created a new school district. That took from portions of the Piedmont, Peralta, and Fruitvale districts representing about 44 children.

The new district was called the Hays School District in honor of the late Colonel John Coffee Hays.

The superintendent appointed the following residents of the area as trustees:

Hetty S. Henshaw gave the district the land for the school. The Montclair Firehouse was built on the spot in 1927, using the front part of the lot.

Requests for bids to build the school were made in July of 1886.

The completed school was small at only 32×36 feet, with just one classroom. It was Gothic in design with a graceful-looking bell tower. It had two entrances, one for the boys and the other for the girls, with each entry having a 6×6 vestibule. The sash bars of the windows are all horizontal, copying the style of European schools.

The construction cost about $2,500 and took about two months to build.

The architects were Goodrich & Newton.

The dedication of the school was held in October 1886. It was attended by most of the families that lived in the area. Judge EM Gibson and W.H Mead made opening remarks. Some of the families in attendance:

The students from the school provided entertainment under the direction of their teacher Miss Lucy Law. The following students performed:

Hays School was the scene of brightness and beauty on Friday, June 14, 1901. Friends and family gathered to witness the closing exercises. The four graduates were:

In 1904, Mr. S. Morrell and Mr. Johnson were appointed to fill the vacancies caused by George Hunt’s and G.W. Logan’s removal.

Attendance for the year ending 1911 for the Hays School was 11 students.

The school was closed around 1913, and the building was demolished. It was probably due to the Oakland, Antioch, and Eastern Railway construction, later known as the Sacramento Northern. For more on the Sacramento Northern, please go here. The East Bay Hills Project

The Montclair firehouse was built on the same site in 1927. The storybook-style building was designed by Eldred E. Edwards of the Oakland Public Works Department.

The nation’s first federally assisted rehabilitation project.

In 1955 a 125 block area bounded by E. 21st Street, 14th Avenue, E. 12th Street, and Lake Merritt was chosen as the “study area” for urban renewal.

In October of 1955, Oakland applied to the Federal Government to formally designate an 80 block area of East Oakland bordering Lake Merritt as its first urban renewal project.

The area was Oakland’s first concentrated action against blight and substandard housing.

Clinton Park was a conservation project, the first of this type in the Western United States.

When the project began in July 1958, the area covered 282 acres contained approximately 1,358 structures and 4,750 dwelling units. Clinton Park Project is bounded by Lake Merritt, 14th Avenue, East 21st. and East 14th Streets

The field office for the project was located at 1626 6th Avenue. The field office, an example of urban renewal in action –was a 50-year old house that was located at 1535 10th Avenue.

In December of 1955, the Federal Government earmarked $1 210,000 for Oakland’s Clinton Park Urban Renewal Program. This amount was two-thirds of the anticipated total cost.

“heart of the Clinton Park urban renewal area.”

The new Franklin School served as an educational and recreational facility and the nucleus of the project. The revised plans for the site called for the additional area and a recreation center to be added. The school replaced the old school building condemned as an earthquake hazard.

Oakland acquired property to double the playgrounds of Franklin School.

The new school opened in September of 1956.

Due to many problems in acquiring property for the expanded facility, the Recreation Center and Playground area’s completion was delayed until the summer of l 961.

In 1956 the Oakland Junior Chamber Committee of the Chamber of Commerce produced a movie on Oakland’s urban renewal program.

The movie, entitled ” Our City Oakland.”

The film (in color with sound)shows examples of Oakland’s slum dwellings, and census figures at the time showed Oakland more than 15,000 such structures (Wow!)

The film also tells of the work in Clinton Park.

In July of 1957, a wrecking crew started the demolition of eight houses near the new Franklin School. This would be the location of the new recreation center.

In 1956, the Greater Eastbay Associated Homebuilders purchased a 50-year-old home at 1535 10th Avenue.

The house was moved from its lot to become an exhibit at the Home and Garden Show.

It was completely remodeled as a part of Oakland’s Operation Home Improvement Campaign.

Following the show, the home was moved to and used as the Clinton Park Project field office.

The office was located at 1621 6th Avenue.

Looks like the house was moved sometime in the mid 1960s. A church is there now.

The homes at 624 and 630 Foothill Blvd

From 1956 to 1962, 57 new apartment buildings were constructed. By 1960 $4,000,000 had been spent on new apartment construction.

The ground was broken in May of 1956 for the first significant construction project for Clinton Park.

Robert A. Vandenbosch designed the 32-unit apartment building at 1844 7th Avenue and East 19th Street.

The three-story structure was built around an inner court that has balconies overlooking the court from every apartment.

A new 12-unit apartment building replaced a “dilapidated” single-family dwelling at 12th Avenue and East 18th Street.

The old structure was located at 1755 12th Avenue, was built in 1900. It had been converted illegally to an eight-unit apartment.

The structure costs $75.000 to build.

In 1958 a new $400,000 apartment was built at 1125 East 18th Street.

Two old homes and their outbuildings were razed to make room for the 40-unit two-story building with parking for the 24 cars on the ground floor.

An eight-unit apartment building at 645 Foothill Blvd was under construction at the same time.

Clinton Park Manor, a 144-unit complex, was built in 1958 at the cost of $1,400,000.

Architect Cecil S. Moyer designed the four three-story structures with a landscaped courtyard in the middle.

The complex is bounded by 12th and 13th Avenues and East 19th and East 20th Streets.

One of Oakland’s first schools, Brooklyn Grammar School, was built on the site in 1863. It was renamed Swett School in 1874, and in 1882 a new school Bella Vista was built there. Bella Vista School was razed in 1951.

In March of 1960, a three-story 48-unit apartment building was built on the northeast corner of 12th Avenue and East 17th Street at the cost of $556,000.

Architect Cecil Moyer also designed this building. The new building contained (it might still have the same layout):

The courtyard had a swimming pool.

Six old homes, some dating back to the 1890s, were demolished to clear the site.

A partial list of the new apartment buildings

In 1960 Safeway Stores Inc. built a new 20,000 square foot building and a parking lot on 14th Avenue.

The Architects were Wurster, Bernardi, and Emmons of San Francisco.

To meet the problem of through traffic on a residential street, which caused neighborhood deterioration. Forty-seven intersections were marked to be altered, either to divert automobiles to through streets by way of traffic “loops.” or slow them down with curb extensions.

The traffic-diverting “loops” will be landscaped areas extending diagonally across intersections.

The result of these intersections was that through traffic in the project area is limited to 5th, 8th Avenues, north and south, East 21st Street, Foothill Blvd, and East 15th Street, east-west.

Diverters were placed at East 19th Street and 6th and 11th Avenues and East 20th Street at 7th and 10th Avenues. Also at East 20th Street and 12th Avenue.

Discouragers were also placed at East 20th Street and 13th Avenue and East 19th Street and 13th Avenue.

Other features of the program included:

By March of 1962, 1,081 structures, containing 3,056 dwelling units have been repaired to eliminate all code. Violation. There have been ll7 structures demolished during the same period.

During this same period, 57 new apartment buildings were constructed within the project area, adding l,l08 new units to the existing housing supply.

Oakland (Calif.). Housing Division. (, 1962). Clinton Park: a historical report on neighborhood rehabilitation in Oakland, California. Oakland, Calif.: The Dept.

Clinton – Oakland Local Wiki

I love Oakland with much of my heart. I look forward to Oakland’s change, growth, virtue, and beauty in the years of the future, glorifying past and forgone years.

My dream is that people who read this book of our city will also strive for a more wonderful Oakland.

By: Jacqueline Taylor

By official proclamation of Mayor John Reading Sunday, October 12, 1969, was the first day of:

“Oakland, The Mellow City Week.”

The observation honored more than 200 eighth-grade authors and artists who produced a book about their home city.

“The Mellow City” was researched and illustrated in the spring of 1968 under the guidance of teachers from Hoover Junior High.

Students were asked to base their work on the response to one question:

“If you were to develop a book to help other students learn about Oakland, what would you include”?

Oakland Tribune

After six weeks of intensive work, they had 76 pages of essays, poems, and more than 50 original watercolors and pen and ink illustrations.

Financing

Money for the project which required field trips, camera equipment, and teacher time was available through Elementary Secondary Education Act funding.

The Oakland Junior League voted to underwrite the expense of printing 2,500 copies.

The students also worked with printers in selecting the paper, typeface and cover design, including

The book is still available (July 2020) to purchase at:

About Open-Air Schools

The schools were single-story buildings with integrated gardens and pavilion-like classrooms, which increased children’s access to the outdoors, fresh air, and sunlight. They were primarily built in areas away from city centers, sometimes in rural locations, to provide a space free from pollution and overcrowding.

Free education and fresh air has interested educators from as far away as Paris, France“

Oakland Tribune – May 13, 1913

The first open-air school in Oakland was established at Fruitvale School No. 2 (now Hawthorne School) on Tallent Street (now East 17th). When it opened, forty students from grades three through seven were enrolled. Miss Lulu Beeler was selected as the teacher because she had prior experience working in an open-air school in the East.

The school was designed to help cure ill and tubercular children. It focused on improving physical health by infusing fresh air into the classrooms and the children’s lungs. The school was established as a medical experiment. It was reserved for children judged to be of “weak” disposition.

The Fruitvale school is decidedly a health school”

Oakland Tribune May 13, 1913

It was constructed at the rear of the playground, one hundred feet from the existing main building.

The square, the wood-framed building, was raised to prevent underfloor dampness.

Each side had a different treatment to reflect the sun. The southern side had tall windows that, when open, didn’t seem enclosed. The east side was opened to the elements with only half a wall. A screen protected them from insects. In storms, awnings could be pulled down to protect the students.

The school was to be the first in a series of open-air schools installed on the grounds of Oakland’s existing city schools.

There were some objections to opening the school, both from the parents of the selected children and the children themselves. The parents did not want their children singled out; the children worried they would be teased as being “sick.” These fears were realized, and the teachers struggled with how to deal with the repeated taunts

The open-air classroom idea was incorporated into many new schools built in the 1920s. I don’t know how long the Fruitvale Open Air School was open. I will update you if I find more information.

Growing Children Out of Doors: California’s Open-Air Schools and Children’s Health, 1907-1917 – Camille Shamble, Los Gatos, California – May 2017

Open-air school – Wikipedia

Collection of Photos – OMCA

In 1951 the students referred to their alma mater as:

“the school that couldn’t stay still.”

Oakland Tribune 1951

In the first 36 years, the school changed location five times and gone by eight different names.

In January 1915, McClymonds High School started in a small building formerly occupied by Oakland Technical High School at 12th and Market with sixty students. Originally called the Vocational High School and was the first public school in California to offer vocational training.

J.W. McClymonds directly inspired the organization of the school, superintendent of the Oakland Schools between 1889-1913 (Oakland Tribune Mar 09, 1924), and the name was changed to McClymonds Vocational School.

In 1924 the school was moved to a new building at 26th and Myrtle, and its name was changed to J.W. McClymonds High School.

It became just plain McClymonds High in 1927. The building was condemned in 1933, and classes were moved to Durant School.

In 1936 McClymonds High School and Lowell Junior High School were merged to form a new high school on Lowell Site at 14th and Myrtle Streets. McClymonds High thereby became a four-year high school.

In 1938 the name changed from J.W. McClymonds to Lowell-McClymonds, then in July of the year to McClymonds-Lowell High School.

Finally, in September 1938, they moved back to the old site at 26th and Myrtle Streets after the buildings were reconstructed at the cost of $330,000. The alumni won out, and once again it was McClymonds High School as it is today.

The new high school occupying the entire block at 26th and Myrtle Streets, erected at the cost of $660,000 was dedicated in March of 1924.

The school was named in honor of J.W McClymonds, who had died two years earlier. The ceremony was held on Mar 09, 1924.

McClymonds High School was completed in 1924 as a part of the school building program of 1919. The new building contained 35 classrooms, 11 shops, administrative offices, storerooms, science, millinery, and art rooms and an auditorium with a seating capacity of 1000. There were shops for forge work, auto repair, machine work, pattern making, woodworking, electrical engineering, and printing. The machinery in the shops costs several thousands of dollars.

The milliner’s art “so dear to the hearts of the fair sex” was introduced as a course for girls in schools of Oakland. Mcclymonds had a shop with machinery for fabricating and molding the millinery.

“The girls are virtually flocking to the new course, which teaches the latest in chic, feminine headgear.”

Oakland Tribune

In 1954 a new three-story reinforced concrete structure was dedicated.

The structure designed for 1200 students and contains 42 classrooms, an auditorium, cafeteria, and library. Corlett and Anderson of Oakland were the architects.

The auditorium is in the two-story south wing and classes in the three-story building.

A class of 75 students was the first to graduate from the new McClymonds High in 1954.

In 1953 the old gym was condemned as an earthquake hazard and wasn’t replaced until 1957.

The new gym was the first Oakland school building to be built with tilt-up wall construction in which concrete wall sections are poured flat on the ground then raised into place.

Folding bleachers will seat 875 spectators. A folding partition will divide the main gymnasium into boys and girls for physical education classes.

The building also included an exercise room, shower and locker rooms, first-aid rooms, instructor’s office, and storage areas. Ira Beals designed it at the cost of $427,000.

The new $625,095 track and field facilities was touted as one of the finest in the East Bay when the it was dedication ceremony was held.

The new tennis courts adjacent to the gym were dedicated to the memory of Earl M. Swisher, a former teacher, and tennis coach.

In 1964 three McCLymonds High School seniors drowned in the icy waters of Strawberry Lake in Tuolumne County.

The victims were:

The trip was for the about 150 students called “honor citizens” because of outstanding community and school service.

Most of the students were on the ski slopes, and sled runs at Dodge Ridge. Between 15 and 20 of them were on the frozen lake when the ice gave away.

The students said there were no signs on the lake warning of thin or rotten ice.

A heroic rescue by three boys and two men saved the lives of at least ten students when the ice broke about 150 yards from the shore.

Carolyn Simril died while trying to pull somebody out and fell in herself.

A large crowd waited in front of Mcclymonds High for the three buses to return. They knew that three students had drowned, but they didn’t know who they were.

More Info:

McClymonds High School is a highly valued icon of the West Oakland community as it is the only full-sized OUSD High School in the region. It is located near the intersection of Market Street & San Pablo Avenue in the Clawson neighborhood, which contains a mix of residential and commercial development with a handful of industrial yards

The school is located at 2607 Myrtle Street Oakland, CA 94607

In this series of posts, I hope to show Then and Now images of Oakland Schools. Along with a bit of the history of each school, I highlight.

Note: Piecing together the history of some of the older schools is sometimes tricky. I do this all at home and online — a work in progress for some. I have been updating my posts when I find something new. Let me know of any mistakes or additions.

Montera Junior High

Montera and Joaquin Miller Schools are located where Camp Dimond, owned by the Boy Scouts, once was. The camp opened in 1919 and closed in 1949 when the board of education purchased the land.

The groundbreaking ceremony was held in December 1957. The school was next to Joaquin Miller Elementary School. Speakers at the event were Peter C. Jurs, board member; Mrs. Robert Hithcock, President of the Joaquin Miller PTA; Zoe Kenton, eighth-grade student; Jim Ida, seventh-grade student; and Supt Selmer Berg. Rev Robert H. Carley led the invocation.

Malcolm D. Reynolds and Loy Chamberlain designed the school. The new school featured: Administration Offices.

The school was temporarily called Joaquin Miller Junior High because it is adjacent to Joaquin Miller Elementary School.

As in all new Oakland Schools, the students, faculty, and community help choose the school’s name.

Recommendations to the school board from the school’s parent-facility club were as follows:

They were set to vote on the name at the next board meeting. Before they could vote, they received a second letter from the parent-faculty club at the school withdrawing the recommendation of Jack London Junior High.

The parents said that.

London was not a fit person for the honor.“

Parent – Faculty

A student representative said, “Montera Junior High” was the top choice for those attending the school. The area was known historically as the Montera District.

The school was formally dedicated as Montera Junior High on November 10, 1959

Montera is located at 5555 Ascot Drive.

In 2011, Montera became a California Distinguished School. The woodshop is another source of school pride, having celebrated over 50 years of teaching children the arts of woodcraft. It is the only remaining woodshop in an Oakland middle school.

I hope to show Then and Now images of Oakland Schools in this series of posts on Oakland Schools. Along with a bit of the history of each school. Some photos are in the form of drawings, postcards, or from the pages of history books.

Note: Piecing together the history of some of the older schools is sometimes tricky. I do this all at home and online — a work in progress for some. I have been updating my posts when I find something new. Let me know of any mistakes or additions.

Sorry I wasn’t able to find any pictures of the school. Let me know if you have any.

The new Columbia Gardens school on Empire Road was a temporary school established in 1961 as a “bonus” project from the 1956 bond issue.

The school was officially named Dag hammarskjöld School after the late secretary-general of the United Nations in October of 1961.

The school was dedicated in March of 1962.

The school is now a middle school called Hammarskjold (Dag) Opportunity and is located at 9655 Empire Road

Lincoln Elementary School is one of the oldest schools in the Oakland Unified School District. The school had several incarnations before becoming Lincoln Elementary School.

Lincoln School’s history goes back to 1865 when the Board of Education established Primary School No. 2, “the Alice Street School,” at Alice and 6th Streets.

The school was moved to Harrison Street and renamed Harrison Primary.

The lot for the first school cost $875, and the two-room school cost $1,324. There were 60 students registered that first year.

In 1872 (1878), Lincoln Grammar School was built on its site at Alice and 10th Streets. They paid $7,791 for the land, and the building, complete with “modern speaking tubes for communication,” cost $20,000.

The 1906 Earthquake interrupted the construction of a new school building with 22 classrooms that replaced the school from 1872. New plans were drawn to make an earthquake-proof structure. There were many delays, but the school was finally open in the fall of 1909.

New Lincoln School ended up costing between $150,000-$175,000.

Lincoln School offered the first manual training and homemaking classes in the city. During the flu epidemic of 1918, meals for prepared for and served to 200 daily.

Preliminary plans for a new two-story concrete building were authorized in October 1957. The cost was estimated at $535 000.

The 1906 building was demolished in 1961 due to seismic safety concerns.

A new building was erected in 1962. The cost of the building was $617,000 and had 16 classrooms, offices, an auditorium, a library, and a kindergarten.

A bronze plaque of the Gettysburg Address was presented to the school.

The school grew and used portable classrooms to accommodate the new students.

The school is at 225 11th St. in Oakland.

The school has a long history of serving families in the Oakland Chinatown neighborhood and children from other parts of Oakland. Today, the majority of the children at Lincoln come from immigrant families across the globe. To learn more about the history of Lincoln Elementary, please visit the Oakland Chinatown Oral History Project.

In 2004 the new annex building was built to replace eleven portable buildings.

Lincoln’s alums include famous Oaklanders: Raymond Eng (first Chinese-American elected to Oakland’s city council), James Yim Lee (author and student of Bruce Lee), and Benjamin Fong-Torres (famous rock journalist and author).

Lincoln School Website – OUSD